A Church of the Poor

Five Takeaways from Pope Leo XIV's Apostolic Exhortation, Dilexi Te

Pope Leo XIV released his first apostolic document on Friday, October 9, 2025, titled Dilexi Te (I Have Loved You): To All Christians on Love for the Poor. Begun by Pope Francis toward the end of his life, the document was completed and promulgated by Pope Leo who said,

I am happy to make this document my own – adding some reflections – and to issue it at the beginning of my own pontificate, since I share the desire of my beloved predecessor that all Christians come to appreciate the close connection between Christ’s love and his summons to care for the poor. [3]

There is much to savor in this document. These five points are just some of my own first impressions.

1. Care for the Poor is the Oldest and Deepest Tradition of Our Church.

The bulk of this document reads like an historical overview of the Church’s ministry to the poor. If at times it feels long and overstated, the point is made abundantly clear: there has never been a time in the history of the Church that ministry to the poor has not been a central factor in her faith life. Indeed, whenever we have seen a major spiritual renewal within the Church, it has renewed and re-centered her focus on the poor, the suffering, the outcast. “When the Church kneels beside a leper, a malnourished child, or an anonymous dying person,” the Pope says, “she fulfills her deepest vocation: to love the Lord where his is most disfigured.” [52]

2. It is “The Burning Heart of the Church’s Mission.”

Pope Leo says: “The fact that some dismiss or ridicule charitable works, as if they were an obsession on the part of a few and not the burning heart of the Church’s mission, convinces me of the need to go back and re-read the Gospel, lest we risk replacing it with the wisdom of this world.” [15]

The “burning heart” reference feels to me like a callback to Pope Francis’s prior Letter Dilexit Nos, in which he quotes St. Bonaventure that “we should not pray for light but for ‘raging fire,’” saying that “the knowledge that Christ died for us does not remain knowledge, but necessarily becomes affection, love.” [DN 26]

If indeed the new document is intentionally recalling this prior one, it makes for a perfect summation of the theme for the rest of the text: that service to the poor is that Raging Fire, the Burning Heart that takes our faith from mere intellectualism to an active relationship of love.

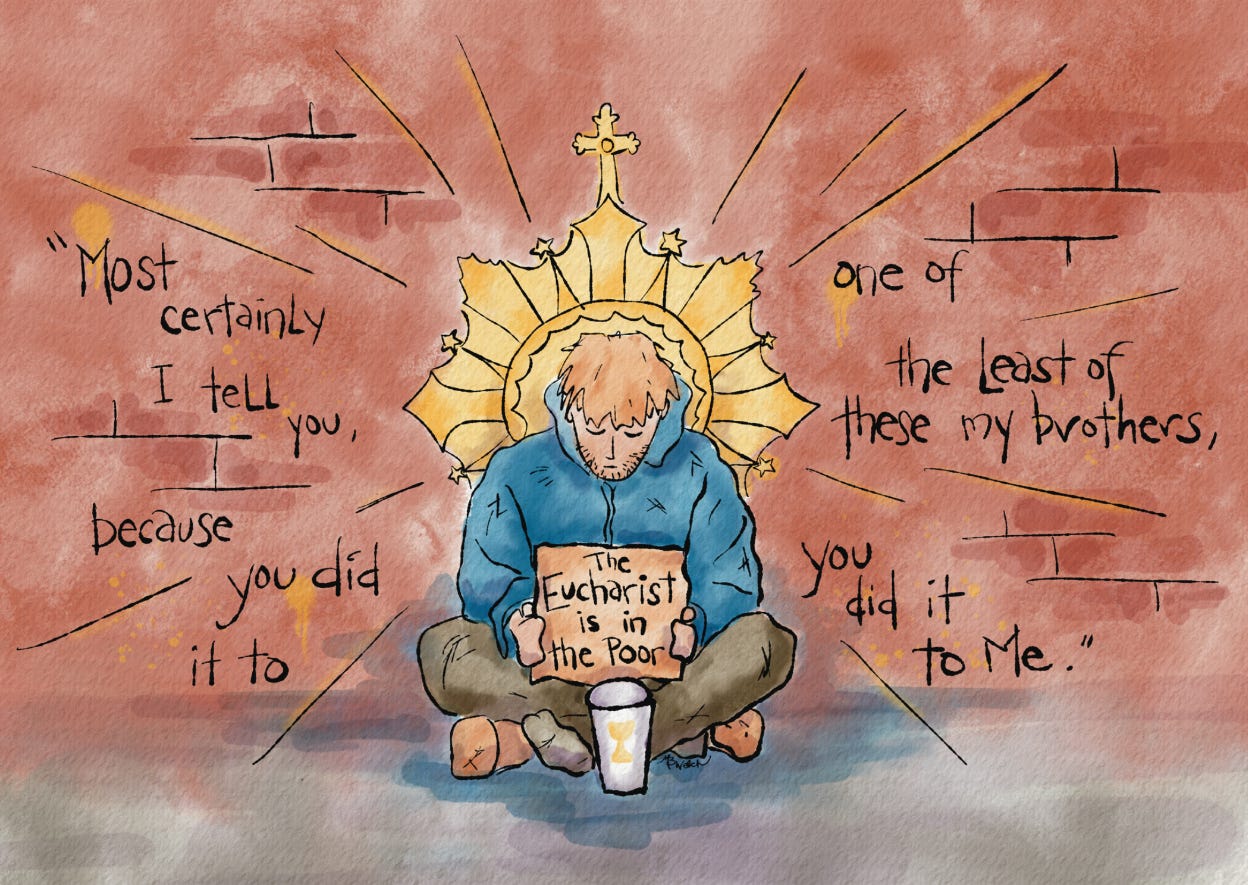

3. Christ Present in the Eucharist is Inseparable from Christ Present in the Poor.

About a third of the way into the document, the Pope gives us an extended quote by Saint John Chrysostom, whom he describes as “perhaps the most ardent preacher on social justice” of the early Church Fathers. Pope Leo presents what I believe is the longest block of quoted text in the document:

Do you wish to honor the body of Christ? Do not allow it to be despised in its members, that is, in the poor, who have no clothes to cover themselves. Do not honor Christ’s body here in church with silk fabrics, while outside you neglect it when it suffers from cold and nakedness… [The body of Christ on the altar] does not need cloaks, but pure souls; while the one outside needs much care. Let us therefore learn to think of and honor Christ as he wishes. For the most pleasing honor we can give to the one we want to venerate is that of doing what he himself desires, not what we devise…. So you too, give him the honor he has commanded, and let the poor benefit from your riches. God does not need golden vessels, but golden souls. [41]

The Pope makes it clear that “charity is not optional but is a requirement of true worship” [41]. It is where we can truly experience a relationship with the incarnate Christ. We can never truly love Christ in the Eucharist if we don’t first love him in the human flesh of the poor and suffering.

4. We Can’t Ignore Structural, or “Social” Sin.

The Pope challenges all Christians to recognize the ways in which our social, economic, and political structures often create and sustain the inequalities that lead to poverty, and to be a prophetic voice against these injustices. “We need to be increasingly committed to resolving the structural causes of poverty,” he says. [94]

He cites Pope Francis’s earlier definition of “social sin” from Dilexit Nos, as a “‘structure of sin’ within society, and is frequently ‘part of a dominant mindset that considers normal or reasonable what is merely selfishness and indifference. This then gives rise to social alienation.’ … A genuine form of alienation is present when we limit ourselves to theoretical excuses instead of seeking to resolve the concrete problems of those who suffer.” [93]

He challenges us to look beyond the explanations and talking points of a society crafted by the wealthy to protect their own interests, to look beyond our own personal comfort and convenience, and to appraise our social structures first and foremost by how they help or hinder the poorest and most vulnerable.

“We must continue, then, to denounce the ‘dictatorship of an economy that kills,’ and to recognize that ‘while the earnings of a minority are growing exponentially, so too is the gap separating the majority from the prosperity enjoyed by those happy few.” [92]

5. We Can’t Neglect the Personal Encounter.

Even as we tackle the social, economic, and political structures of poverty, it is vital that we never let “the Poor” become an abstraction of numbers and statistics. The Pope reminds us that the poor are “not a problem to be solved, but brothers and sisters to be welcomed.” [56] We need to encounter them as individuals, people with their own human dignity, their own needs and wants and dreams and desires.

No Christian can regard the poor simply as a societal problem; they are part of our “family.” They are “one of us.” Nor can our relationship to the poor be reduced to merely another ecclesial activity or function. In the words of the Aparecida Document, “we are asked to devote time to the poor, to give them loving attention, to listen to them with interest, to stand by them in difficult moments, choosing to spend hours, weeks, or years of our lives with them, and striving to transform their situations, starting from them. We cannot forget that this is what Jesus himself proposed in his actions and his words.” [104]

Pope Leo goes on to encourage a renewal of the ancient practice of almsgiving, “which nowadays,” he says, “is not looked upon favorably even among believers. Not only is it rarely practiced, but it is even at times disparaged.” [115] But it is, he tells us, the most direct way of achieving that basic human contact with the poor in our midst.

Almsgiving at least offers us a chance to halt before the poor, to look into their eyes, to touch them and share something of ourselves with them. In any event, almsgiving, however modest, brings a touch of pietas into a society otherwise marked by a frenetic pursuit of personal gain. [116]

Pope Leo has given us a firm reminder that our faith is not one of rules and dogma, but of a personal and intimate relationship with our incarnate God. “To enter into this great mystery,” he says, “we need to understand clearly that the Lord took on a flesh that hungers and thirsts, and experiences infirmity and imprisonment.” [110] He reinforces the basic truth once expressed by St. John Chrysostolm: that if we cannot find Christ in the poor, we can never know Him in the Eucharist. This prophetic call to be a poor church for the poor is the key to the spiritual renewal so desperately needed in our Church and in our world.