Right and Just

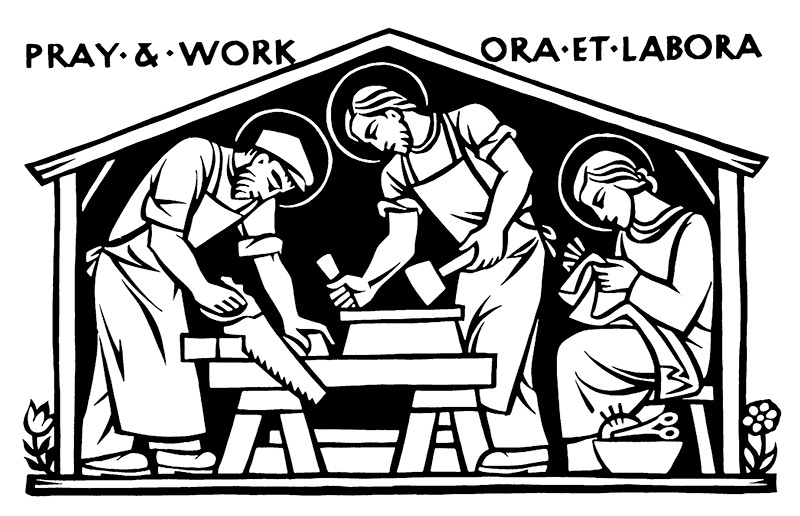

The Feast of St. Joseph the Worker

May 1st is celebrated in the Church as the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker. It’s a day to celebrate the dignity of work and the rights of workers. I came across this homily from a few years ago - it wasn’t intended for St. Joseph the Worker’s Day, and it’s not for the readings of the day (it’s for the readings of Sept. 24th, 2023, which you can find here).

But it does tackle one of Scripture’s most challenging labor-related passages and seems appropriate to the theme of the day.

Today we get one of the more challenging parables of the Gospels.

With this parable, more than any other, I hear people saying, “You know, I know I’m not supposed to – but I actually kind of agree with the disgruntled workers.”

Because we’ve all been in a situation like that, of being part of a group project or a workplace team, and feeling like that one guy did almost no work but got just as much credit, and darn it that just doesn’t seem fair.

Of course we understand that in these parables, Jesus is speaking metaphorically about the Kingdom of God – preparing us for something completely beyond our human understanding, by using ordinary everyday imagery that we can all relate to. And most of the time we have no problem understanding that he’s not speaking literally.

But this parable is different. This hits us right in our sense of justice.

In the first reading God tells us through Isaiah, “my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways. As high as the heavens are above the earth, so high are my ways above your ways and my thoughts above your thoughts.” And this parable really drives that point home.

I heard it said recently – I don’t know the source but it stuck with me: “None of us sits high enough to look down on others.” God, of course, does sit high enough to look down upon us all, and from His vantage point the distinctions we make among ourselves seem less significant than we make them out to be.

I find it telling that when the disgruntled workers complain to the landowner, their complaint is, “you have made them equal to us!”

It’s a complaint that Jesus himself hears often throughout the Gospels, when he eats with prostitutes and sinners the Pharisees and religious leaders object – not in these words but in spirit; “you have made them equal to us!”

In our own culture, this seems to be a particular obsession. People can get very worked up about the possibility that some others in our society might be getting something they don’t deserve. We need a “them” who should not be made equal to us. We want to cling to this idea that maybe all men are created equal, but some are more equal than others.

Those workers who had labored all day in the fields see a bunch of latecomers showing up at the last hour getting the same pay as they got. But the landowner, representing God in this parable, has a different perspective.

Maybe the landowner, going back to the marketplace throughout the day, saw a bunch of laborers, all ready and willing to work, all with the same needs, all trying to get enough to make it through another day; to take care of their families for another day.

When he hired those first workers at the start of the day, they made an agreement about how much they would be paid. When he went out later in the day, he promised only to “give them what is just.” But “just” by whose standard?

Clearly those who worked the whole day would consider it just to apportion it according to hours worked. And the landowner, in paying the workers for the work done, might also find this to be most just for his own interests. Certainly it’s how most businesses nowadays choose to pay their workers.

Even those latecomers themselves – in the midst of their frustrations about not securing a full day’s work, their worries about how to make ends meet on only an hour’s pay, I expect most of them would understand that it’s fair to get less pay for an hour’s work.

That’s fine for our worldly sense of justice. But this is about God’s sense of justice.

The social teaching of our Church makes the point that a just wage is what gives a worker enough to support himself and his family. Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Rerum Novarum in 1891 wrote “that remuneration must be enough to support the wage earner in reasonable and frugal comfort.” In God’s eyes, it is just that everyone gets what he needs. He makes “them” equal to us because their needs are no less than ours.

All this takes the parable at its surface level. We’re approaching it as a straightforward story of a landowner’s labor practices and how he pays his workers. But of course, Christ’s parables invite us to dig deeper, to understand what it tells us about the Kingdom of God.

And in this sense, people generally understand it as an illustration of God’s divine mercy in the salvation of all the world, a salvation that is given equally to all who come to him. At the end of our lives we can all enjoy his bountiful mercy, no matter how long ago or how recently we accepted him. God’s salvation makes us all equal to one another.

The parable does not limit itself to either the literal or the metaphorical interpretation, but challenges us as an example of “both-and.” Both the worldly and the other-worldly understandings have something to tell us.

Saint Paul speaks of this tension – of longing to join Christ in the next life, though he recognizes the work still to be done in this life to prepare it for, to reconcile it to the next.

We often pray, “thy Kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” And parables like this challenge our understanding of how the two work together.

Jesus begins the parable by telling us that the Kingdom heaven is like – not will be like this. We may not be living in the ultimate realization of God’s kingdom, but Christ’s challenge to us is to begin working now for that eventuality.

We are challenged today to consider who these “them” are in our own lives. Who do we try to set ourselves high enough to look down on? When Jesus tells us that the first shall be last and the last shall be first, who do we really not want to see moved up to the front? What group of people might prompt us to complain to God that he’s making them equal to us?

And can we hear the landowner – hear God – asking us, “are you envious because I am generous?”

Jesus shows us how the way of the world we live in is at odds with the way it will be – the way it should be – the way God intended it to be. And he invites us to learn to live as if we were already there.