The Conscience of the King

Homily for Sunday, February 16, 2025: Sixth Sunday of Ordinary Time

Cursed is the one who trusts in human beings … blessed is the one who trusts in the Lord. The Prophet Jeremiah sets up this dichotomy which carries through our readings today. As I meditate on this, I’m reminded (yet again, yes…) of one of my favorite Catholic figures of the Twentieth Century.

As a young woman, Dorothy Day was a Communist and a political activist. After she became a Catholic, she says, one of her friends from those days remarked, I always thought you were too spiritual to be a good Communist.

Even in those early days, long before her conversion, Dorothy writes that she was drawn to the Catholic Church – just to go in and spend time sitting quietly in that sacred space.

And the more time she spent there, the more she came to notice the people there. The poor, the workers, refugees and immigrants, those who made this their spiritual home.

Her political activist friends always had a lot to say about these groups, about what’s best for them and what they need. But here in the Church was where she actually encountered them.

In politics, they were problems to be solved – issues to be debated. In the Church they were brothers and sisters to be loved and served. This, I think, is why politics and religion never quite fit comfortably together.

Cursed is the one who trusts in human beings, says the Prophet Jeremiah in today’s first reading. And even when they profess a faith in God, it seems the politically-minded have trouble breaking out of that mindset.

We’ve all heard the accusations; that Pro-Life doesn’t care about the child after it’s born. Or that the Church is less interested in humanitarian concerns than its own bottom-line. Such a cynical outlook is unfortunate, suggesting a heart too steeped in worldly concerns to be open to the true generosity of the Christian spirit.

If there is a role for religion in politics – and I believe there is – it should be to serve as its conscience.

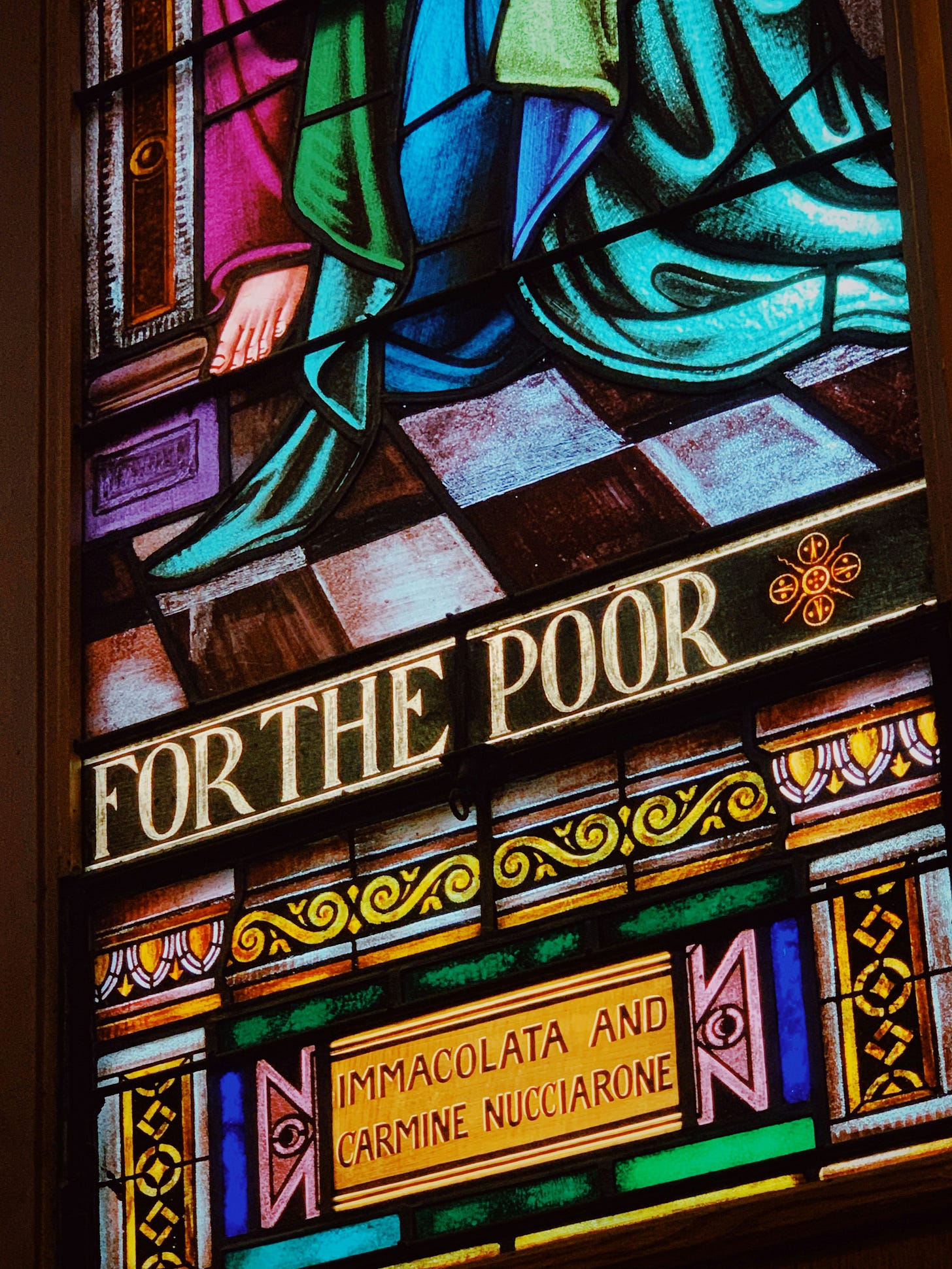

The Church instructs us that all political and economic policy should be oriented first and foremost to the good of the poor, the vulnerable, on helping those unable to help themselves. In a world where the rich and powerful guide lawmakers to serve their own best interests, we have a vital moral duty to preach our Preferential Option for the Poor.

I’ve read somewhere that, if there is disagreement or division within the Church, always look to the poor. Wherever the poor are, that’s where Jesus will be.

Jesus tells us, Blessed are the Poor, a sentiment we’ve heard before in Matthew’s Gospel, in the Sermon on the Mount. But Luke’s Gospel doesn’t water it down – no “poor in spirit” here, just blessed are the poor. And Luke throws in an extra twist: Blessed are the poor, but also, woe to you who are rich.

Blessed are you who are now hungry, for you will be satisfied. But woe to you who are filled now, for you will be hungry.

Blessed are you who are now weeping, for you will laugh. But woe to you who laugh now, for you will grieve and weep.

A reminder, perhaps, that our situation in this life is fleeting. What hardships we endure now are temporary; what good things we have now will pass away. The more we try to cling to the good, or to fend off the bad, the more we frustrate ourselves. The more hopeless it all seems. The more cynical we become. That is the curse Jeremiah warns against: the curse of the one who trusts in human beings, who seeks his strength in flesh, who turns his heart away from the Lord.

Human institutions will always be subject to human frailties. Even the Church has always had more than its share of human weakness. But throughout her history, we see reformers like Francis of Assisi bringing her back to the basics – back to the Poor. Where are they struggling? What makes their struggles worse? What can we do about that? Who is helping them? How can we join in those efforts?

Jesus tells us blessed are the poor, and he offers them the Kingdom of God. If we hope to be welcomed with them there, we must be open and welcoming to them here - to those who are poor, hungry, hurting, despised, and persecuted. Those we would rather not deal with. Those we might cross the street to avoid. They are Jesus in our midst. And at the end of our days, when we approach Jesus at the Gate, and they are there beside him, will they welcome us in?